In a dimly lit room in west Kabul, stacked with shelves full of books, a small crowd gathers around the warmth of a gas heater. Books clamped under their arms, they are eager to share the stories they’ve read over the course of the week.

Members of Afghanistan’s youngest reading club, the Book Cottage, range in age from four to 13. The club is just one of many reading circles that are springing up across the capital and reviving a book culture that, once lost, is now vibrant, liberal and expanding once again.

“You have to start them young,” explains the initiative’s founder, 25-year-old Mashed Mahjor. “The country is still at war, so children don’t have a lot of opportunities to talk freely and ask questions, especially girls. We have to bring our book culture back to life.”

After starting the reading club six years ago, she now has up to 20 regular members – and hundreds of book donations from all over the world.

Afghanistan has a long literary tradition, but also a history of destroying and burning books. During the Taliban era, whole libraries were looted and demolished. The books that reach the country remain subject to a rigorous censorship process.

At 31%, Afghanistan has one of the world’s lowest literacy rates. The rate among women is lower still, at 17%.

But trends are shifting. In west Kabul, a neighbourhood with laid-back coffee shops, small startup businesses, a quick-growing dating scene and – at its heart – Kabul University, reading circles for all ages are expanding. They have started to provide a platform for Afghans to discuss, in a mixed-gender environment, issues not on the public agenda of a conservative society.

“We talk about topics such as hedonism, pleasure, even sex and desire. In a segregated, conservative society, these discussions can’t happen without an agenda, and books provide just that,” says Syeda Quratulain Masood, who has been researching Kabul’s book culture for her PhD at Brown University in the US.

“Books clubs are an indicator of a young generation that has come of age after 9/11. Many have liberal leanings and seek a space where they can talk openly. During the Taliban, Kabul University’s library was destroyed, but it has come back to life.”

One such space is found in a basement room of one of the city’s universities, where a group of up to 20 book lovers meets weekly. Some travel the length of the city to participate.

“It’s worth it,” says Attash Mashal, a civil engineer and government employee. “Most of the books we read can’t be accessed in Afghanistan, so we search for them online and print out copies. We read novels, poetry and philosophy.

“This one is censored though,” he adds, holding a copy of Albert Camus’ The Fall. “We just found out.”

With many books in Iran translated from English into Persian, censorship is on the agenda each week. Paragraphs discussing controversial subjects or topics such as sex and religion – and even whole chapters – are often entirely removed.

“The abrupt silence gives an indication and a curiosity to dig deeper,” says Masood. “We always compare the translations with the original texts and they can vary significantly.”

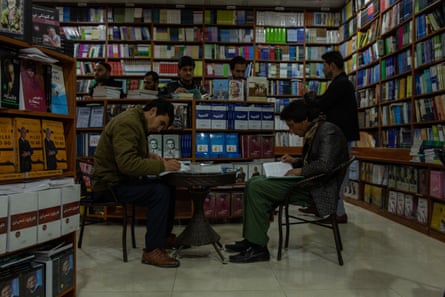

Yet it’s the translations that most people are after, as it can be difficult to read books in English or other languages. At Aksos, the city’s biggest and most diverse book store, people squeeze into the tight space, examining new titles, reading in corners, or taking selfies against a backdrop of bookshelves. Books are the new cool.

Aksos holds anything from The Kite Runner – another book previously banned in the country – to The Daydreams of Ashraf Ghani, the country’s president.

“Once again, the city is boasting poets, writers and creatives pushing against the recent norm,” says Masood.

“I think it’s because in book clubs, or when writing poetry, we can share our ideas and beliefs without restrictions,” says Yalda Heideri, a student in her twenties who attends a university book club.

“Afghanistan has restricted us a lot, especially us women, so we found a way to have discussions that would be embarrassing or even impossible outside.”

But for Heideri, literature has also become an escape from daily life in a wartorn country where there were 3,804 civilian deaths last year, according to the UN assistance mission in Afghanistan. “When I get tired of it all, I escape into poetry. It’s a whole different world. Kabul is improving and becoming more open, which makes me hopeful. But regardless of where peace negotiations are going, we have to find our own way to cope, and books are just that for me.”

According to Masood, it’s exactly such discussions about conflict and terrorist attacks that can help people on a daily basis. “People connect books to their own lives. They learn how Europeans have also lived through conflict and take messages from it,” she says.

Qanbar Ali Zareh, a 43-year-old father who has taken his daughters to the Book Cottage, says that books help him understand his own life better. While waiting for his children, he sits in a corner, reading Michelle Obama’s Becoming. “It’s the same story, but a different face,” he says. “I faced isolation and discriminations throughout, so this books speaks to me. It’s very personal. She’s a remarkable woman and I want just that for my daughters: for them to raise their voices and to read books.”